The Roots

The house is high up there, on the peak, in Castelvetro di Modena. The mounds of soil tell lots of tales, the earth “knows”. Here, the countryside has soft and welcoming curves, just like a “zdora”, the proverbial Emilian housewife. They fought here, back in the Etruscan times, and there was a stronghold: it isn’t surprising that, centuries later, history presented its bill and the land started erupting old tombs.

Oscar Scaglietti talks about it with a hint of pride. “If I want to plant a tree, I need to ask for permission, because when you dig something else could come up. My father bought the house in the ’60s. We lived here from March till December, there was enough room here, for everybody. Here I had my young children skiing and sledging, and here they became fond of skiing. Can you see down there? Yes, it’s a little hazy today, but when it’s clear, I can see the Alps, Mount Baldo and the Euganean Hills from here. And then the Apennines, the mountains above Sassuolo”. Oscar Scaglietti talks with endless love about the land – his land – and the reason why is clear. In his tale, you breathe a dialectic made of confines and horizons. The Scaglietti family comes from the land, and their link with roots – a sort of farming leitmotiv, in filigree – is visible. The roots though are not to be meant as a dead weight, but as the line of a kite, which enables you to fly high but safely.

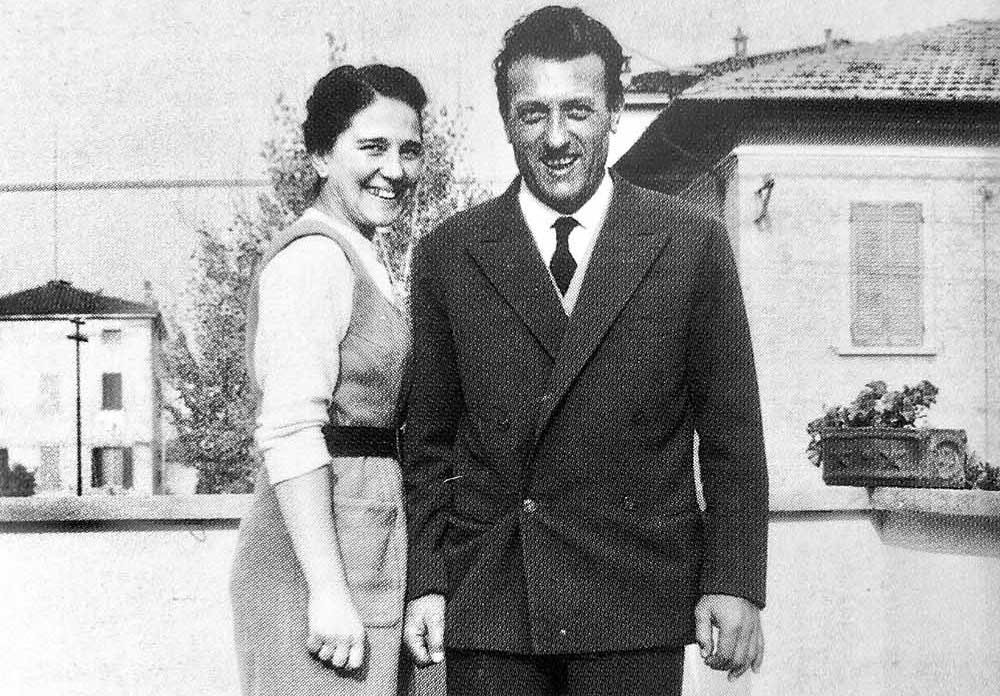

The land is a “mother” and Oscar starts his tale talking about his mother. “my mother has always greatly supported my father: through tranquillity and security. They always got on well, you know? My mother never complained, even if we always had people for lunch and dinner. For us, work has always been group work and she was one of the group because she understood its needs”. When he talks about her, Oscar lights up. “She was my point of reference in the family, there was a strong trust between us, I was an open book with her. I talked to her about everything, even about my first experiences with women. My mother was the one who convinced my father to buy this house, you know? She came from a family of farmers”.

However, your father – the great Sergio – also came from a family of farmers. He was born in a hamlet in the district of Tre Olmi, next to the Secchia river; when Sergio was a child, he used to paint the tractors’ models in red, his favourite colour. Sergio was only thirteen when he started to “learn the job” – as an errand boy or “factotum” – in the body shop. In winter, the road from that new world to the countryside home seemed endless, foggy, dark. The small Sergio walked it with racing pulse and with a five Lira silver coin under his tongue. It was the weekly pay and it was worth a treasure: it would have been a disaster if someone stole it! Who would have thought that that scared child would have become the patriarch of a body shop which would have made the history of cars.

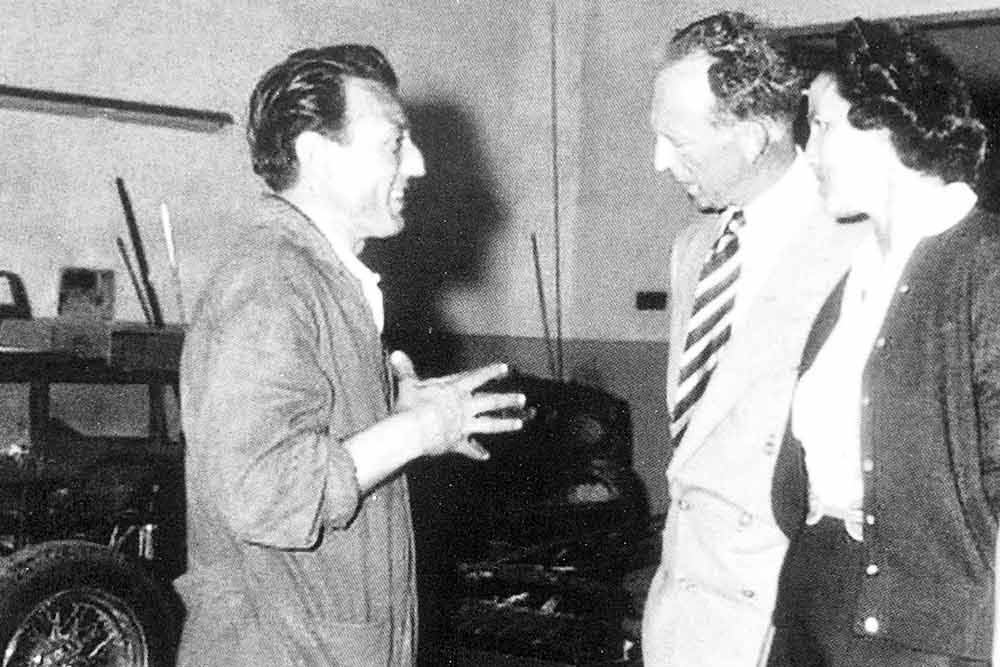

Success came without knocking on his door: on the other hand, it is always like so. Through the years, the Scaglietti e C. would become “Scaglietti” full stop, with the split from Marchesi e Sala. In the meantime, the head offices were moved to San Lazzaro as a change, where the neighbour was nonetheless than Ferrari. For Sergio who loved red as a friend and who was enraptured when he saw a car that colour, Ferrari was the magic forge: the enchanted palace par excellence. But how could he leave an impression on that man, who was already an out-of-reach legend for us? One afternoon, the right chance presented itself. Oscar still remembers it.

– My father was always there, looking at the cars going in and out and, when the chance occurred, he went to Ferrari to make small repairs: a lock, a bonnet. That is when he said: “One day I want to make one of these cars!” and, at a certain point, that day came.

– What happened?

– A Ferrari client crashed against an electricity pylon: the car was destroyed! The car’s owner’s name was Alberico Cacciari and he was a metal sheet manufacturer, who was fond of races. Luckily, Cacciari remembered that he saw my father’s body shop right in front of Ferrari’s, so he came asking him to fix his car. “What do you want to fix, if you wish I’ll make it new again”, my father proposed, adding: “Actually, if you give me ten aluminium sheets, I’ll make it even lighter!” Said and done: the old bodywork was discarded, with its heavy tubes and my father put together a nice car. At that stage, Cacciari brought it to the front, to assemble the engine and the mechanics and he took advantage of that to praise us: “Look, Ferrari, look what a nice car the guy in front of you made for me!” When they tried it, it actually drove better than the others because it was a lot lighter too… So, Ferrari crossed the road and told my father “Can you make a few like that one for racing for me, do you have time to? Do you think you could manage?” My father didn’t need him to say it twice: he split from his brother and with another two people who worked there, he hired three guys and they started off like that, with six or seven of them. It was 1953: I was eight years old.

Following in your father’s footsteps isn’t easy, partly because a father like Sergio was busy at all times and because – which is something that everybody who lives the situation of a family-run business will know – in such contexts of excellence, the concept of “big baby” or mama’s boy doesn’t exist at all. Actually, quite the contrary, Oscar talks about himself with uttermost honesty.

– My father started off with a lot of courage: he had a wife and two children, which meant that he worked day and night.

– How do you remember him, back then?

– Look, I’ll tell you something. Once I saw him with the moustache and I didn’t recognise him. I hadn’t seen him for so long, that the person I had in front of me was a stranger. I also cried, then he went to shave his moustache off and I stopped. I didn’t recognise him as he worked all the time.

– Were you born in San Lazzaro?

– No, when I was a child, we lived in my paternal grandmother’s house, but my cousins lived there too and so, one day, we understood that we couldn’t all fit in there. So my father thought about moving to Tre Olmi, where my mother’s sister and father lived and we lived there for four to five years. Then, we moved to Modena, because my father spent too long travelling to the workshop and we moved to San Lazzaro, where I started the second year at primary at the nuns. From the school window, I could see the Ferrari workshop courtyard. When I had time, I cycled to my father’s workshop, to watch them making cars.

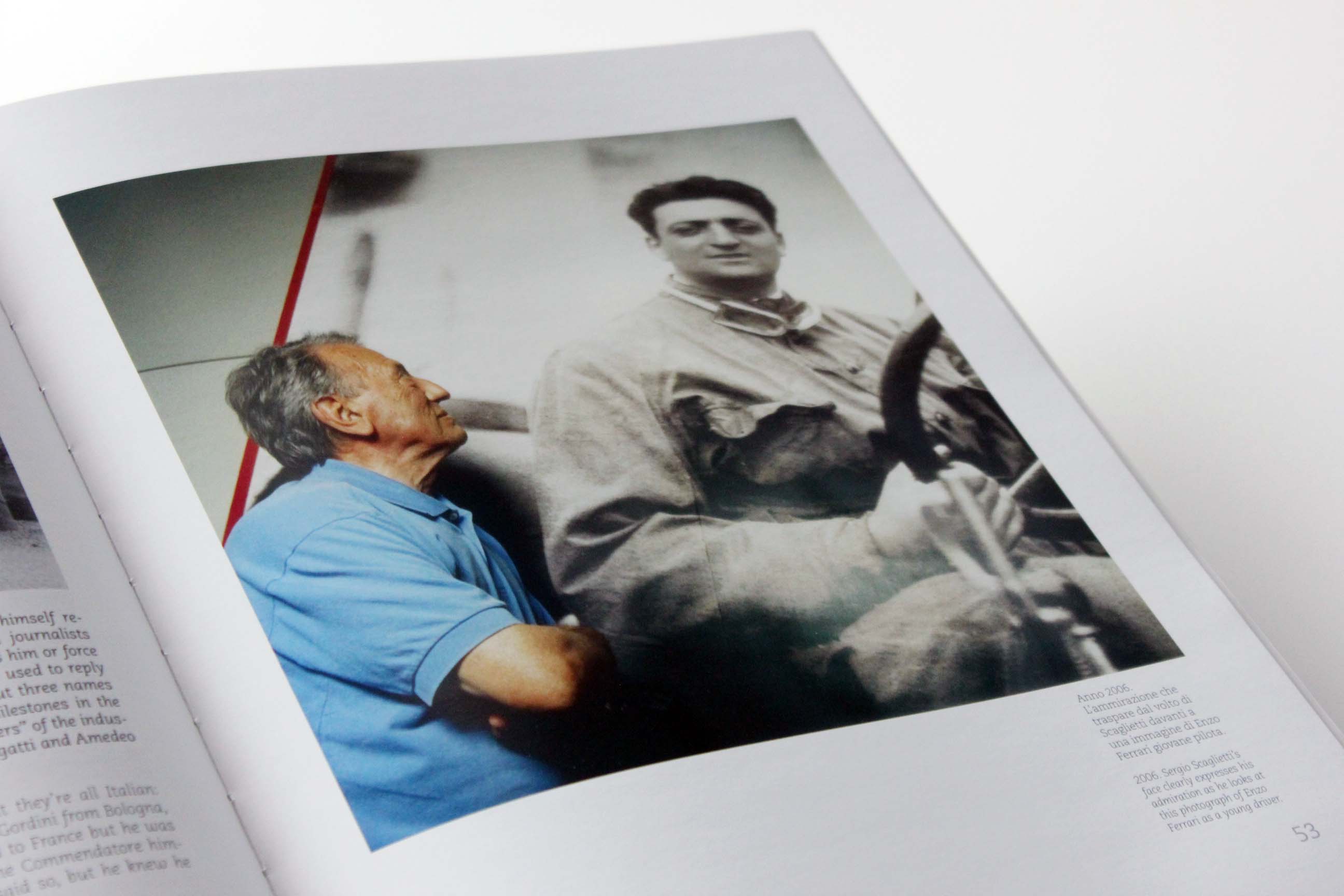

– Yep, Ferrari. How did you see him back then, when you were a child? He must have not had an easy temper… I wonder how many times you would have seen him argue with your father.

– Will you believe me if I said that I never saw them truly falling out? Just a few squabbles, such as “I told you to do this, you always do as you please!”. Such things. Then, a few minutes later, Enzo would call my father as if nothing happened, and used to tell him “Come on, come here as I need you”.

My father called him “the big man”! I used to think to myself: he has some ideas… he’s a bit of a dictator. I mean, I was intimidated by him. He looked sourly, cruel. Then, little by little, he proved himself to be a wonderful person: but only with a selected few! He was close to us and he told us about his own stuff. He came every morning. He went to Antonio’s to get his beard shaved, then he went to the cemetery and, on the way back, he came to see us. We only spoke in dialect. Often, he had us accompany the clients. Sometimes he had some of them take a drive on his coupe, just to let them hear the engine. You should have seen the clients who came off the car with all of the hair straight on their head! Once in a while, from mid-July to the end of August, the Drake didn’t have his cook, so they came to ours in the countryside: they placed the driver and the body-guard under the oak tree. They met with the knight commander Barilla, who brought maccheroni and tagliatelle. There was also Cremonini, the one who owned the meat empire. The entrepreneurs from Correggio came, as well as those who helped us with plastics and they told each other their own stories from outside work. Listening to them was beautiful, they brought up some fantastic anecdotes! They talked about visits from kings and other people, in a different way to how they were told in the magazines. They were magnificent days.

– Anecdotes aside, can you remember what they talked about?

– Sure! It had been a few years since the early years in San Lazzaro. You heard things about the progress made by industries, the investment strategies… I liked listening to them because, as a greenhorn, I learned things that they would have never taught me at school. Specifically, I remember the period of the major strikes between ’68 and ’70, when some entrepreneurs threatened to shut down because they said: “If we cannot rule our companies, there is no point in investing money, which will need to be shared with the trade unions”. Such things made me think: how can a young person who has just started working for the company, hear about an entrepreneur who’s about to shut down because the trade unions are a tough cookie? However, in most occasions, they talked about new projects: about what they could do to improve contacts with suppliers and clients, to have a dynamic expanding company, not like a small shop, but with a more open mentality. There were some who thought about how to set up a better work organisation, etc.

– And how did the Drake deal with the situation?

– Enzo Ferrari tried to understand how he could improve his relationship with the employees. He was a hard nut with the trade unions, but in the end, he made concessions for the company’s own good. “If the workers are happy, it benefits me” he used to say. There was a time where basically the manufacturing halted because there was a strike after another: alternated work, one-quarter of an hour on and a quarter of an hour down.

We had 65/70 employees who had to make 7/8 cars a day. It wasn’t easy. Yes, we nearly had to shut down shop: the trade unions were very tough around here. When there were company negotiations, things got resolved, but when they wanted to make national agreements with different realities, they ended up causing massive contrasts all over Italy. Our company always went well, until the trade unions merged together.

– How did your father deal with this situation?

– Well, as chief of the group, dad used to say: “Okay, I’m fine with giving you a pay rise but please, you have to work, I want you to be present and please be careful to work safely.”

– Did many of them strike?

– The employees were half and half. If you want the full story, the slackers were the ones who struck the most. All of that happened in ’68 and it lasted for many months, then, in ’73 and ’74, my father invited the trade union representatives to sit down around a table. He didn’t want things to take a turn for the worse. “We don’t want someone to end up dead in front of the workshop”, he used to say.

By International Classic, written by Martina Fragale